The co-founder of Gusto on the founder mindset, when startup success doesn't feel right, and the importance of taking time away from work.

For weekly recaps of The Macro, sign up here.

The Macro : Gusto has grown a lot since you launched out of YC almost four years ago under the name "ZenPayroll." Nearly 30,000 companies have joined your platform, which now also handles benefits and compliance, and you've attracted more than $150 million in funding.

But to start, we'd like to rewind a bit. Why did you decide to start a company in the first place?

Joshua Reeves : Well, to go way back, I'm a local -- I was born in San Francisco and grew up just north of the city. But my parents were both transplants. My dad is from Pittsburgh and he came out to California in the 1970s. My mother is from Bolivia. She came to the U.S. at 18, and had to learn to speak English and everything. They both studied at the University of San Francisco, which is where they met. They went on to be teachers.

When I think about entrepreneurship, I think of it as a mindset. It's not necessarily about building a company. It's about not accepting the way that things work now, and instead thinking of how it could work. I think my parents both moving to a whole new place was always a huge inspiration for me: Learning a whole new language, adapting to a new culture. People that move to a whole new place by definition are open to taking more risks. That choice to build a whole new life somewhere has to be driven by a conviction to change something -- the status quo would have been for them to go with the flow of how things are already done, what they already saw life to be like.

I've always wanted to take after them. For me, that's meant starting a company.

Looking at your bio, I noticed that you studied Electrical Engineering in college. How did that end up with you creating a software-based payroll platform?

Joshua : Yep. Actually, all of the Gusto founders studied EE. As an aside, one summer I worked as an intern at Intel, in the fab. As an EE major I felt like a kid in a candy shop, surrounded by billions of dollars of equipment. I remember the first week I was there, I was in a clean room in a semiconductor fab, in one of those bunny suits where you can barely see a person's face. Someone else in one of the bunny suits walked up to me and said, "You must be new." And I said, "Yes, actually I just started this week." And he said, "I could tell, because you're smiling way too much."

Anyway, in school I did a double concentration of EE with signal processing, which is a lot of math. At its core, it's about, "How do you take systems that are complex and simplify them in terms of the few things that matter?" I think that was really helpful for me. The heart and soul of a startup is having a lot of things to do and figuring out what are the few that matter the most.

Was Gusto your first startup?

Joshua : No. I started a company in 2008 that was an app publisher platform. The Facebook app platform had just launched, and at that point, if you wanted to build an app for it you had to have $20,000 to hire a developer or basically have a friend who was an engineer to help you out. So I teamed up with a former college classmate, who had been working at Google for the previous few years, and made a platform that had templates to let people build apps themselves.

How did that go?

Joshua : It was pretty successful. At one point there were 40 million people on the apps, we were making thousands of dollars a day in ad revenue. We were acquired in 2010, and I went on and worked at the acquiring company for a year.

But it didn't feel quite right. Today, I realize that it was because the business was reactive, rather than proactive. It wasn't clear what our ultimate goal was. We were just optimizing on making more money. Our main metric of success was revenue -- there was no sense of, what's the real impact on the world, or why does this matter? What's this going to look like in 10, 20, 30 years? Looking back, I think that created a lot of discomfort for us.

Don't get my wrong: By all means we were very fortunate and it was a great experience in a lot of ways. But it should have felt more successful. There was clearly something missing.

Is there a concrete lesson you took from that experience?

Joshua : Oh, there are a lot.

One thing I like to recommend to other founders, and really everyone -- it's important to create time for introspection. It took a few months of being introspective after I left the company for me to be able to say that the whole experience wasn't quite right, and pinpoint why.

When we're in school, you have some of that built in, with summer breaks and the semester system. In real life there isn't a structure like that. 20 years could pass without you asking yourself, "Is this how I should be spending my time?"

For me now I have a structure of my own: On Sundays, I always step away from work and technology for a few hours to spend some time in nature and go for a hike. And at Gusto we have something we call the "fly away program," where everyone on their one year anniversary gets a free plane ticket to go anywhere in the world. There's been 100% usage of that. There's always so much to do and things are intense, especially when you're working at a startup. It's important to force yourself to step away.

So how did Gusto come next?

Joshua : All of those past experiences were the catalysts for Gusto.

For one thing, I realized that good startups exist to fix something -- some fundamental problem that the founder cares about so deeply and is so obsessed about fixing that they have to start a company to do it. I knew that if I was going to recruit a team, and hire people, and raise capital again, I'd have to be able to say: "Here is my 20 or 30 year mission."

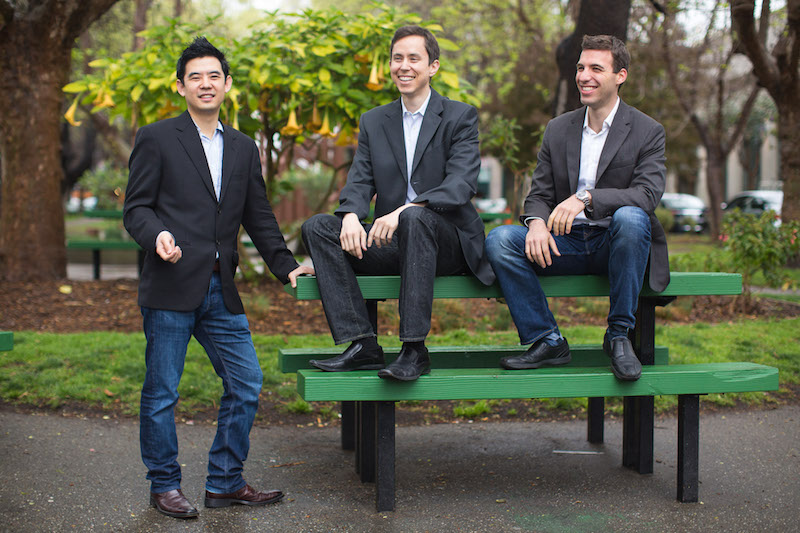

Tomer [London], Eddie [Kim] and I are the three co-founders of Gusto. We had all been very close friends through the years. We had all run companies before, and we knew what a problem it was to do payroll and HR documentation. Each of us also had family members that had worked with or in small businesses for a long time: Eddie's mother runs a small doctor's office, my mother-in-law does payroll for a company down in San Jose, Tomer's father owns a store. We knew firsthand that for many people, this was that "hair on fire" kind of problem, and that building a solution would be so helpful. We knew this was a mission we could be really passionate about.

Something I'd say to any early stage founder is, imagine this is the 10,000th time you're describing what your company is doing. Will you be as excited telling someone about it then as you are now? Sitting with you today, this is probably my 500,000th time describing Gusto, and I never get tired of it. You can quickly suss out whether your idea is simple revenue arbitrage or business optimization, or something that's a real problem.

How did you know you were onto something?

Joshua : I'd look at our customer list, and see all these different kinds of companies -- there were Silicon Valley tech companies, but also a bakery in Los Angeles, a flower shop in Texas. It was cool to know that we were helping all of these companies treat their employees as more than just a number. We weren't just focused on optimizing revenue; being proud of how we earned that money was just as important.

And as co-founders, when the three of us were together it never felt like a job. During YC in the early days, we were all living together in this one apartment, and Eddie's bedroom was actually just a closet. But it never felt like a burden to do it. Working together was direct and transparent and honest.

We knew that when we added new people to the team, we'd have to work really hard to keep it that same way the best we could.

Any advice on how you've done that?

Joshua : I personally made the hiring offers for the first 60 people in the company. We have a few hundred now... so obviously, that does not scale. But generally, I think that companies too often focus solely on skill sets. I think values and motivation are just as important. In interviews, I've found the easiest way to segue from someone just listing their accomplishments into discussing what they really care about: I channel my inner three-year-old. I just keep asking, "Why?" That helps get to the bottom of things, to motivation of why they do things, not just what they do.

Another thing I've learned is that repetition gets a bad rap, but it's actually a very good thing in a quickly-growing company. You can have this great conversation over the course of several days about a decision or process, and come to a unanimous conclusion. Then two weeks later, someone new can join the team and ask, "Why do we do X this way?"

It's important to not get exasperated when that happens, even though it's easy for everyone to start to feel like an old-timer very quickly at fast-growing startups. Repeating ourselves can be valuable. It can help us realize if we need to change, or take another look. It's almost always a good conversation to have.

Fast forwarding a bit, it was recently announced that Gusto had raised a new round of funding at a reported $1 billion valuation. Do you have a way that you think about fundraising, or something you've learned along the way?

Joshua : We've always viewed fundraising as another form of hiring. You can actually apply the same lens as you do to hiring an employee. The person becomes associated to your business in such an important way.

Too often, founders think, "Let's go get money!" instead of, "Who do I want to work with?" When you're hiring someone, you usually do it in two stages: The first is generally talking about life, work, passion, motivation, skills. Then the second stage is more of a deep dive into how things will work and doing due diligence. When people are talking to investors, a lot of times they jump straight into stage two, and get into these shotgun marriages.

You don't want to be in a situation where it feels like an obligation to keep in touch with your investors or to listen to their advice. Imagine that you had an employee to whom you had to give useless busywork to keep them engaged. That would be absurd. I've made it a point that all of our investors are people that I'm excited to talk to.

This is especially important in the early days, at the seed round. Ideally, you find the people who you would pay to give you advice, and instead they're the ones who give you money.