When Dave Messina entered a graduate program for genomics in 1998, he was elated. He was taking the first steps of what could be a career at a top-tier university, working on scientific research that could impact millions of lives.

For weekly recaps of The Macro, sign up here.

But while his chosen field had so much promise, he realized that for him, the academic environment might not.

“I looked around, and saw that some of the smartest scientists I'd ever met were having trouble getting funded, and moving forward in their research,” Messina says. “The life of an academic scientist is really hard. You’ve got to really, really want it. And even then, for many people it just doesn’t work out.”

Messina quickly realized that the best way for him to succeed in the field of genomics might be to work outside of academia altogether. At that time, though, there wasn’t a clear path to follow.

“I thought, ‘Maybe I can get into a company, and move my way up so that I can dig into important research there.’ So I talked to a lot of people,” he says. “They all knew of someone who had tried it at a larger biotech corporation, but it definitely was the exception.”

So Messina created the path for himself. He eventually pulled back from the PhD track in genetics at Washington University in St. Louis, and instead obtained a Masters Degree. He went on to earn his PhD in computational biology, opting to concentrate on the software that does the heavy lifting in genome analysis. And in 2012, he joined RNA sequencing software startup Cofactor Genomics, where he now serves as COO.

Today, Messina says that startups are an increasingly viable place for the kinds of research careers that used to be found only in the ivory tower and big corporations.

He’s not alone in that belief. Y Combinator has funded an increasing number of startups with biotech and life sciences applications, many of which are led by founders who have crossed over from years in the academic realm. Since 2014 alone, more than 24 startups with a biotech or life sciences focus have launched out of the YC program. The wider field of Silicon Valley investors has also developed a heightened interest in the space, with firms such as Andreessen Horowitz launching new funds dedicated entirely to investing in biotech and life sciences startups.

Below are some insights and lessons learned from several founders from this new breed of science-oriented startups on how to navigate the path between academia and Silicon Valley.

Analyzing risk

The first step for many people leaving the realm of traditional academic research and entering the startup space is assessing the risks of making such a change. The odds may not be as daunting as they may expect.

"Coming from academia, there's a myth that it's really risky to join a startup, and in my experience that's not true at all," Messina says. "It depends on the field, but look at the Genome Institute at Washington University in St. Louis, which is a premiere organization. Just a few weeks ago, they didn't get a big grant that they were expecting to get, and they had to lay off 20 percent of their workforce. The good news now is that there are companies and startups around who are hiring those people."

That said, there are a number of options for scientists to weigh. "You don't have to jump in all the way and say you're going to start a company immediately. There's a whole continuum," Messina says. He recommends that current PhD and postdoctoral candidates take on part-time roles at startups through programs such as the St. Louis-based BALSA Group.

For those who have decided to launch a science-oriented startup, it's also important to consider the inherent risks of your product and approach.

"If you're someone coming from a PhD or postdoc background with an idea for a startup, it's so important that you reduce your technical risk," says Max Hodak, the co-founder of robotic bio lab startup Transcriptic. "Otherwise, you might spend a lot of time and money trying to find some novel pathway, and then find it's not there."

Not being clear-eyed about your startup's technical risks could lead to a crunch in funding, Hodak says. "Venture capitalists say they want to invest in hard tech, but VCs hate technical risk. They're comfortable with market risk, but technical risk is really difficult for them to reconcile. In biotech, a lot of founders have more technical risk than they think they do."

Adjust your time scales

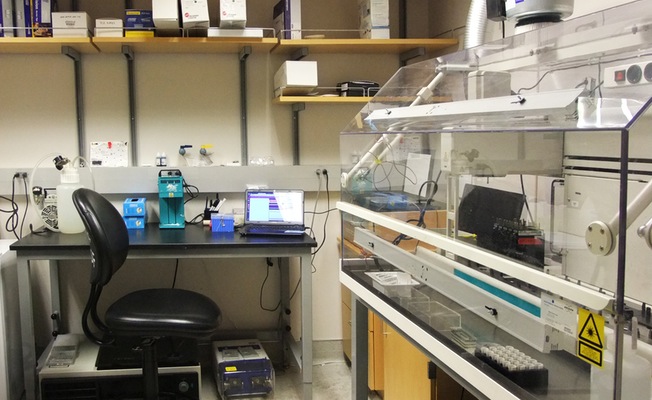

Thanks to advances in both computing and equipment, it's now affordable for startups to perform the kinds of lab research that would not have been possible outside of large institutions even five years ago, says Matt De Silva, the founder of personalized brain cancer treatment startup Notable Labs. But, he says, there are key differences in how a lab should operate at a startup versus a traditional research environment.

"There are certain aspects of academia that are very useful in a startup: the creativity, the looking at things from first principles, the open-mindedness," De Silva says. "But the big challenges are the time scales and the quality expectations. For a startup, work needs to be both faster and more rigorous than an academic lab. In academia, in order to publish a paper, often you just have to get it to work one time out of ten -- so you think, OK, I'll just keep doing the experiment until it works. We need it to work nine or ten times out of ten. If something from a paper doesn't bear out, the impact can be mitigated. If you have a product you're developing, it can be a disaster."

Jessica Richman, the co-founder and CEO of human microbiome testing startup uBiome, agrees. "In academia, it's not uncommon to get a different result than expected and say 'Okay, let's come back to it in a month, and let's discuss it then.’ At a startup, that really doesn't work. You can wait and come back to it that afternoon, at the latest,” she says. “Think about what a 'hacker' was to traditional computer scientists. Startups need the life sciences equivalent of that."

Communicate your idea

"The cultural differences between academia and startups cannot be overstated," uBiome's Richman says. "I tell scientists to approach the startup world like an anthropologist would: Read all the books you can, learn about the culture, observe the people, figure out how they do things. A lot of the books you’ll read will probably have bad startup advice, but you'll get a picture of the thought processes and the language."

Coming from academia, where projects are funded by grants, it can be a big change to go into investor-funded startups. "It's important to learn how to tell the story of a business, as opposed to the story of a grant," Richman says. Often, people successfully secure a grant by describing things that have been proven in existing scientific literature, and highlighting how their project fills a gap in the research that's been done. Startup investors aren't typically impressed by that narrative, she says. "The story of a business is about vision and progress: What are you going to do, how far have you gone so far, and how are you going to make money."

She says that the mores around raising funding are different from grants, too. "The whole funding environment for startups can be hard to navigate. You're used to applying to grants -- there's no having lunch with someone, they turn you down, but then they talk to a friend, then you hear that their friend wants to invest," Richman says. "In academia, there's no wheeling and dealing around the grant process. It's important to get used to that. I'll talk to founders who are coming from academia about their fundraising, and they'll say, 'I talked to 3 people and they all said no.' That's not how it works. You need to talk to 300 people. It's a sales process. Getting startup funding isn't about applying for something and sitting back and waiting."

Nailing communication is also key for hiring. Transcriptic's Hodak says that if you can quickly and clearly communicate what your startup does to someone without a life sciences or biotech background, you may find that it's easier to hire engineers than you might expect. "Sam Altman told me once that it's paradoxically easier to do a 'hard' startup than an easy one, because people want to help you. I've found that to be really true," he says. "I can't imagine in this environment trying to recruit for a social mobile app. That would blow my mind. But it's easier to get really good people when you can tell them you're building robots that are furthering the field of science."

Notable Labs' De Silva says that his company’s first full stack developer hire actually reached out to them, after reading about Notable’s mission of helping find a cure for brain cancer in the press. "There's a growing group of software engineers who are tired of using their skills to optimize ads,” De Silva says. “If you can communicate that if your company is successful, it will be directly impacting people's lives, great people will want to help you achieve that."

What shouldn't change

For all the differences between the two sectors, there are some things that should not change as scientists enter the startup environment.

"As the tech world is blending into the biotech world, founders and investors need to be conscious that the burden of proof in science is very high, and that won't change," Notable Labs’ De Silva says. "If you're a startup in this space, you need to be transparent, you need to run trials, you need to show your science works in all the same ways that traditional institutions have. Talking a big game, being secretive, and raising a huge amount of money sometimes works in software and web tech. But it's an inverse playbook in biotech. The stakes are higher, and people will hold you to that, as they should."

According to Transcriptic's Hodak, maintaining a healthy respect for the complexity of science and instilling it into the non-scientific team members and investors is crucial. "For people not coming from a science background, it's easy to underestimate how difficult these things are,” Hodak says. "There are a lot of people from the tech sector seeing the opportunities here but underestimating the technical complexity. Yes, there's a lot of opportunity, and a lot of improvement to be had, but it's very complicated in non-obvious ways."